|

I was invited to Montpellier university in the middle of May 2022 to speak at a conference on participatory theatre and community plays. In preparation I wrote these notes

FROM COLWAY TO CLAQUE In the past few months, I have been focussed on writing my book on community plays, it’s a cathartic experience I always knew it would be a process that throws up as many questions for me as answers. It’s come at a time too when I have been exploring methods to collaborate and devise with communities at a deeper level and to give people greater collective investment in the process. My approach since Ann Jellicoe wrote her Community Plays and How to Put Them On has changed radically and are still evolving so I can but give you a snapshot of where I am. Each successive project is informed by the lessons of the previous ones, so things are always evolving. So, if you are looking for a method there really isn’t one to be had. I’m not the same person I was yesterday and after today I hope and expect to have new perspective because of all of you. Listening is a great part of working with communities on developing a play. I’m an improviser and listening in improvisation is regarded as a willingness to change. That should be true of life and that’s what I’ll be doing. They say an expert is someone who's made more mistakes in their field of work than most, which is encouraging it means I might be a genius. I took off the directorships of Colway Theatre Trust in December 1985 so I think I should start with saying just a little about Ann. Ann Jellicoe is universally recognised as the founder of the contemporary community play. The term was first coined in 1979 to describe The Reckoning, a play Ann had just finished directing for her home community, Lyme Regis. Ann was a relative newcomer to Lyme Regis she arrived after more than a decade in London in the 1950’s and 60’s. She had come to fame as the first woman to have a play produced in the main bill at the Royal Court Theatre, the first woman to direct a play at the Royal Court, the first woman literary manager of the English Stage Company. The Sport of My Mad Mother, her first play had a profound impact on British Theatre and paved the way for other women playwrights Her next play The Knack, became a Broadway hit and a film version won the Palme d’Or. She was among the group of leading playwrights of her generation, but by 1976 family was taking a priority she was feeling disenchanted; it seemed to her the same audiences were trotting from theatre to theatre, whilst theatre didn’t seem that important in most other people’s lives. Less than a year after moving to Dorset she got the idea of writing a play for the school her children were attending. She wanted to base the play on the town’s history so enticed a few local people to help with the research. The story required a lot of adult parts, so decided to involve the parents, which prompted her to write the play with some one hundred characters. performance workshops began drawing in more townspeople she instinctively didn’t want to turn anyone away, so the project became fully inclusive. No-one imagined it would eventually involve hundreds of people. She persuaded her professional friends to form a small production team, barely paying them their expenses. Exeter University drama department provided a stage management team and lighting equipment for free. The project was affectively growing spontaneously, a response to one decision influencing the next. She worked around setbacks as they occurred or turned them to her advantage. For example, it became obvious that the school stage couldn’t hold the now 90 strong cast, so she reshaped the staging to seat a third of the audience on back of the stage and building stages around the perimeter of the hall leaving an empty space in the centre to accommodate the audience. This established principle of promenade theatre. Decisions emerged as much out of the pressure of natural forces than by design. It was described in one press article in its simplest term as a play for, by and about the people of the community, although the prepositions ‘for’ ‘by’ and ‘about’ can be challenged, but it paved the way for an increasingly democratic approach. The Reckoning was intended to be a one-off but when Ann realised that she had in fact created a new theatre form, at which point she established the Colway Theatre Trust to develop the form. Between 1980 and 1985 Ann directed three plays and mentored and produced four others The projects began to display recurring features, and her method became more defined. It wasn’t too long before professionals who had been working on Colway play projects began to do their own. I was one of them. Having seen Ann’s third community play I persuaded her to take me on as her assistant director for her fourth. By 1985 I was working on my second independent play when Ann called to tell me that the Regional Arts Council was cutting her regular grant by half, and despite a strong public campaign she had lost the battle and was now going to resign in protest. but not before taking on her most ambitious project to date, David Edgar had written Entertaining Strangers for Dorchester. Ann was asking me if I would co-direct it with her and then take over the helm of Colway Theatre. Following her resignation Ann wrote Community Plays and How to Put Them On describing her discovery and journey into community plays. At the end of the preface, she wrote “This book seeks to provide a model: you can imitate its practice or create your own… At its simplest the process boils down to credibility: can you deliver and convince others that you can? To discovering how to involve people in creating a work of art, and where to draw the line between the needs of the community and the needs of art.” This is a recognition by Ann that she was only at the beginning of an evolving process but it’s also an invitation to the next generation to develop it further. What was distinctive about Ann’s approach was the idea that you don’t have to compromise on art because you are working with a community and it’s thanks to Ann that where she ended was a starting point for us. In the 37 years since, the world has changed, and the work has evolved radically as I think she would have wished No-one can do Community Plays like Ann, so while she invites us to imitate her if we like, none of us can. The kind of the director or writer as an individual practitioner is a big factor in defining what a community play is, equal to the unique qualities and circumstances of the specific community they are working with. Their values fundamentally define the nature of the project’s process. Because community plays are personal and specific it makes it very hard to define generally what a community process is or how democratic they are. I can only talk about community play that are particular to me it might be useful to briefly identify some of the influences. My father was in the Air Force so we were constantly moving every two years This may contribute to the conflict I have toward envying people with roots, who grew up in the community they were born and my contentment with solitude. Basically, I love the idea of community, but I don’t want to live in one. I retain a deep scepticism about the education system. I believe passionately that we are all born with tremendous natural capacities but lose touch with many of them as we spend more time in the world. Ironically, the major reason this happens is education. The result is that too many people never connect with their true talents and therefor don’t know what they’re capable of achieving. I see the community as a vehicle for self-recognition, and personal growth and undoing some of the damage done. School at least gave the barest handful of certificates paradoxically to train as a teacher at the Frobel Institute. Froebel believed that a young children learn best in settings that provides a stimulating and prepared environment where they can explore and learn from their own experiences and perspectives. It was at Froebel I was for the first time in the presence of a great teacher Sybil Levy. It wasn’t so much what she taught, but how. I know now that she manipulated our environment and dropped things in front of us like traps for us to discover. I realised to truly grow and find yourself you needed skilled guidance. Whilst there is discomfort, and criticism around the notion of a professional hierarchy, in a community play I believe good leadership paradoxically can help safeguard greater demonocracy and its our job to facilitate that. I got a teaching job in Sunderland close to where Dorothy Heathcote was teaching a full-time Advanced Diploma course at the University of Newcastle. She was developing revolutionary dramatic inquiry approaches to teaching and learning, using irole-play, as a teaching tool. Basically, giving children simulated life experiences to motivate enquiry. I used it in my own teaching, eventually getting a job as an educational drama advisor teaching teachers to use drama in this way. It’s essential tool now in getting for getting large groups to role play in sessions we call drama searches. They help us collectively ‘find the play’ or inspire the writer. I got a lucky grounding in improvisation working with Roddy Maude Roxby during late 1970’s and running a course with Keith Johnstone when I first took the helm of Colway. Improvisation has been transformative for me in developing an improvisational mindset in teaching, directing, writing and in life. I now have an improvisation community around me, some of whom who have been working with me for over twelve years, we are now regularly performing fully improvised ‘plays in the moment’. So, these influences have an important personal bearing on my approach. A community plays generally start either by my responding to an invitation or by identifying a community. I get to know a community through running a pilot project that also allows me to conduct a study that ascertains whether a play is both suitable and feasible. The projects go under the banner of empty gallery, the same principles of a play apply but the final product is converting an empty shop or other space into community devised exhibition, interactive installation, or immersive performance environment. The projects all involve group collaboration. The most valuable characteristic of community plays is that most of our work involves people working with groups. I believe groups consist of however many individuals there are in the room plus one, and that one is the group mind. If we can be aware of the group mind, then the characteristics of the group is especially stimulating – it consists of many voices. If an individual were to speak as groups speak, we would think them crazy. Groups can simultaneously take you to different places and engage in a whole host of contradictory activities. Consequently, it disobeys rules, contradicts itself, is restless, delivers the unexpected, is spontaneous, takes you places you wouldn’t normally go – these are qualities you need to be creative. This is not a metaphor for individual creativity - groups have the characteristics of groups and individuals have the characteristics of individuals. A group throws you into being collectively creative in ways you can’t achieve individually. Groups are far less patient than individuals, which is a virtue in developmental terms. Groups are, more impulsive than individuals . I find individuals are more of a problem than groups. I am genuinely more comfortable working with a group than I am with an individual. I deal with casts of 120 quite happily and can feel sometimes uneasy with a solo actor. Individuals are too emotional; you spend years trying to get them over their habits, blocks, and resistance. The beauty of a group is that there is less resistance, because groups don't behave that way. They are more reckless, less resistant to change, by being reckless the group is more open to transformation. Individuals are much more conservative. And here is the thing: Contrary to this being a denial of the individual the nature of groups challenges and develops the individuals within it, in ways they wouldn’t alone, it’s also an acceptance of individuals as social beings rather than people in isolation. Groups give individuals courage to take bigger risks because, paradoxically, they feel there is safety in numbers So back to the play we finish the pilot project and if the play looks suitable and feasible. We hold a public meeting after the pilot project has been presented. We present the idea of play and a feasibility report. It may include local advocates, others from precious play projects to say something about their experience. We will hold a vote and if the meeting votes ‘no’ that’s the end of the affair. If they vote ‘yes’, we hand out volunteer forms which explain all the potential activities people can sign up for. We now form a Steering Committee to help manage and oversee and proactively support the whole project. We have developed a community play board game the covers a large hall floor and the team spends a half day minimum going through a simulated eighteen month play project, solving problems. Creating imaginative initiatives, designing posters, making paper costumes the idea is to finish the game with as many community points as possible, and within budget. During the pilot project we will have started soundings and will be continuing with them during the set- up of the play project. Soundings are brainstorming, exercise, game-based techniques to help the community identify contemporary issues and select the most potent or pressing and explore its complexities. They will then research to find events from their local history that resonate with the contemporary themes. These will become the focus for developing the play. We also set up a devising or play development team which replaces the old research team. This team is really two levels, a small group who manage the script development, assess where we are, promote the workshops, set up the rooms gather material we might need. They are practical hands on. The other team are those who attend and participate in the drama searches and devising and development workshops, they are both tasked based. The Drama Searches are powerful role-playing simulations of an imagined world that can accommodate large groups. We select some time and place in the community’s history. We may start in a large circle with everyone imagining and describing the place and times we want to take ourselves to. I’m relying on the whole group’s knowledge. On the Isle of Sheppey, when we were exploring a famous mutiny, we first imaged the dockside in 1800 then we took up actives of mending nets, gutting fish, dockyard watchmen looking out for trouble. Later we were sailors huddled in cramped, wet and rat invested bays on the lower decks of ship complaining about conditions and I was provoking them in role to mutiny. Participants improvise their roles in the make- believe world and in this way can immerse themselves and experience other people’s lives together I take the role of facilitator to animate the drama guiding or challenging them moment-by-moment or releasing information gradually and indirectly. They must work at solutions, and gain understanding by reflecting on what’s going on, and think about the consequences of the decisions they take; and so find meaning for themselves. Although the writer is present at the Drama the Search we never talk about the play, the focus is always on the event in hand. The Writer is a vital part of the process and is there to ask questions, participate, suggest an event or a moment to explore improvisationally. If the community identify with people of the past, it inspires them to research between sessions either to prepare the next Drama Search or in response to the previous which has perhaps prompted deeper research, maybe into actual individual characters, or checking historical accuracy. Devising and Script Development begins as the writer feels the urgency to start writing Devising takes the material from the Drama the Drama and other various sources and transforms them into the medium of theatre so has a different intention. My aim is not to impose of my ideas but evoke and implement an inclusive collaboration of many contributing minds. Devising’s eclectic and unpredictable nature makes it impossible to reduce it to a fixed method. I may begin with broad plan, but I will expect diversions because I know progression will emerge from moment-to-moment through improvisations, play and conversations. Collaboration can fill the room with a multitude of possibilities that gives us opportunities to move in many different directions and produce a range of creative solutions beyond the scope of an individual. There will an interchange of ideas with the writer with greater focus on plot, creating-characters, genre, the writer giving structure, and incorporating their unique style. The relationship between writer and community is a negotiation based on mutual respect. Neither the revelations of the community in their search should be negated nor the integrity of the writer be disrespected. There will be discussions and experiments about scenes that can show rather than be told Devising involves same elements that the writer, composer, designer, director employ to do their various jobs: characters and their point of view and objectives, plot or storyline, form, framing devices, audience role and so on. There are really no rules but there are principles such as First get on your feet Committing around a common purpose Doing the Research Keeping Records Keep an open mind Constructive Pressure A willingness to fail is an obligation Respecting individuals Listening to the group as separate identity Once the play written and read publicly to the town, inclusive casting takes place, if you show up you’ve got a part. At casting everyone is measured for their costume, they fill in an availability form so their rehearsal schedule can be designed to suit their lifestyle, no easy task. Around thirteen weeks before the performance date a professional theatre team become resident in the town. The size of the team and the length of rehearsal time are determined by the budget and community needs. The production team mostly consists of a Director/Writer Project Coordinator, Designer, Design Assistant, Production Manager, and a Musical Director. But other roles may be required Rehearsals Twelve-week rehearsal period begins, we may have as many as four spaces in different parts of the town of various sizes, and the performance may be in a school hall, a church, an industrial warehouse a tent whatever is available. The play office opens to the public. A Design Studio opens in an empty industrial warehouse, or an empty shop in the town centre. It’s open to public six days a week, where they can arrange to work with the designer on specific projects or drop in ad hoc. The community is invited to help build sets, props, and costumes with the guidance of designers and production manager. Workshops are taken into schools and other establishments. Small scene rehearsals happen nightly and on alternate Sundays the whole cast gather, and the fragmented scenes are linked together. Two weeks before opening night, we start building the scaffolding stages and rigging lights. A week before we hold full cast rehearsals every night. The performances run for twelve consecutive nights. The productions is presented in promenade style. The space, a school hall, is transformed with a series of stages around the circumference. There’s limited seating for disabled and elderly audience members who need to sit down at the back of the school stage, but the majority are expected to stand with the cast in the central area. The action of the play, with casts, of over a hundred and twenty swirls all around and through the standing audience. We put the audience and performers in a shared space, so the audience are no longer silent witnesses in the dark but become a major scenic element as much in evidence as the performers, the become part of the world of the play. Entirely new relationships are possible, there can be face to face social contact between performers and audience; voice levels and acting intensities can be varied, the sense of a shared experience is felt. In a promenade play we find that the audience quite naturally press in close during intimate scenes and moves away when the action becomes broad. Usually, they willingly give way to the performers and re occupy areas after the actions pass through. This does not result in chaos; rules are not done away with they are simply changed. The audience are participating in the shaping of the spaces. initially the audience may be nervous. One way of breaking down barriers is to have performers staff the box-office, play host and greet the audience socialise and advise them on where best to see the show. The audience need help in making the connection between their experiences at other popular entertainments, religious observance, and festivals. They are knowledgeable about what to do they just don’t know it. Sometimes we achieve this by holding a real fair at the start, so the audience are clear about ‘how to behave’. The difference between the community actor and audience is clear because of costume, but no attempt is made to hide the non-performing life of the actors. The audience and performers collectively form the community. To emphasise our belief that individually and collectively people can make a difference we implicate the audience in the action of the play where we can. Implicating techniques includes treating the audience as 'other'; giving the audience another roll or identity; taking part physically; Moving them away from spectator into witness. In the Minneapolis play ‘Flying Crooked’ a play that explored class in America depending on which door they entered through the audience were treated either as a guest at a society function or destitute street people under the rail arches. A fence divided the space in half it was noticeable how this opening experience altered their points of view to the events in the drama. Implication is not only more powerful than preaching but helps us avoid taking the moral high ground. Implicating should lead to the audience toward making choices not ultimatums. The moments where we implicate the audience directly is no longer acting for, but in a confrontation with the audience. In Out of the Blue, a character speaks to the audience as if they were fellow villagers and invites them to adopt three orphan girls and save them the horrors of the workhouse. Actors were briefed to withhold volunteering and await audience intervention. Participation can disrupt the prepared rhythm or even line of a scene and its uncertainty can be quite frightening for the cast, they resist events that disrupt prepared rhythms. Once we involve them at this ‘higher level’ we try not to let the audience off the hook. For me the final and greatest achievement are those nights produces the feeling that cast, and audience have created a performance together as one community.

2 Comments

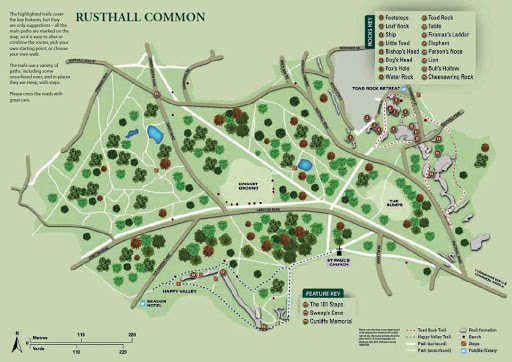

On a recent walk-about Happy Valley with David Brett we made this Dandelion line on a rock in the potential site our our last scene We had technical problem with our last Devising Session on zoom because we couldn’t open the breakout rooms so couldn’t meet in smaller groups. People are naturally less reluctant to speak in larger groups; its not easy in any event because zoom has this small delay and people occasionally speak over each other as a result. However we managed with zoom as we always do. The devising group have been amazing, patient, imaginative and loyal, and new people joining, which is great. So here are the notes from the Music and Verse delving session and the provocation for the next one. Over the next four devising sessions we will be developing the plots of each our our four stories and discovering how to tie them together in a final scene. PROVOCATION FOR DEVISING - THE STRUCTURE OF THE PLAY

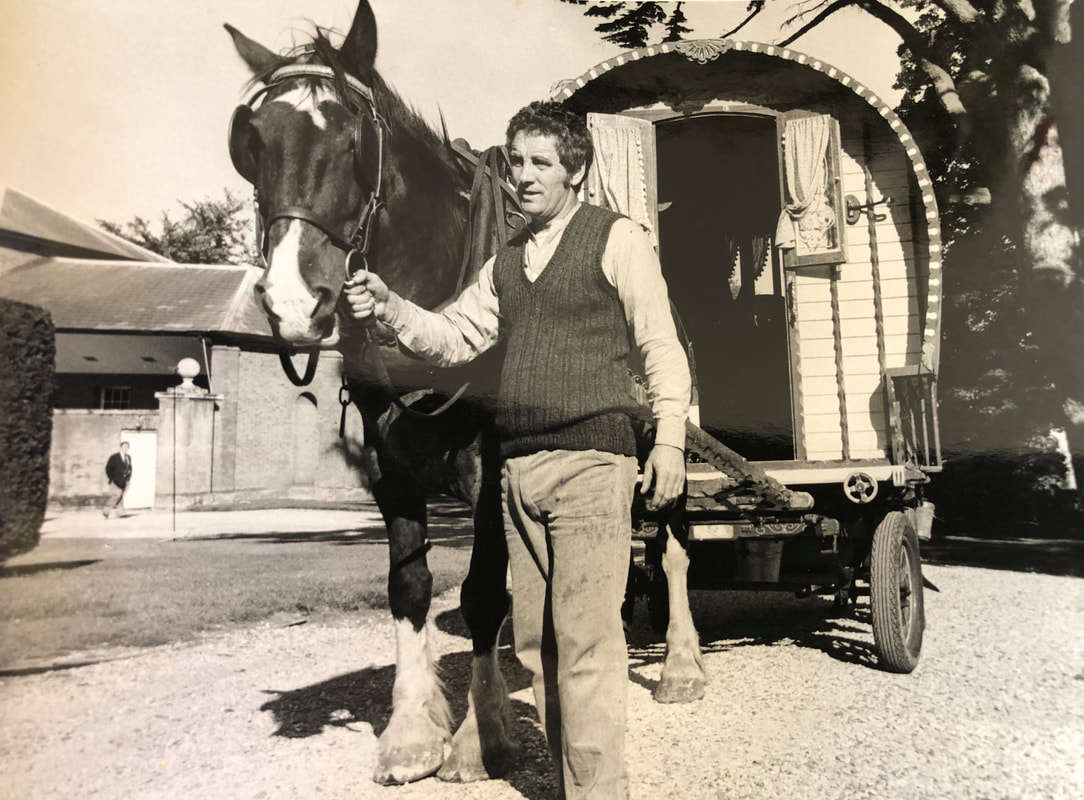

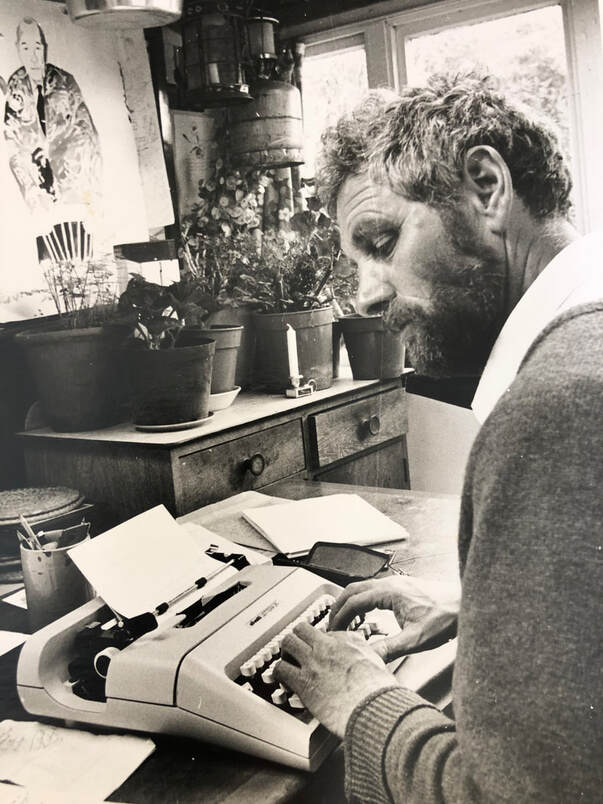

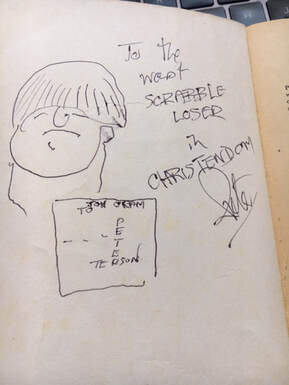

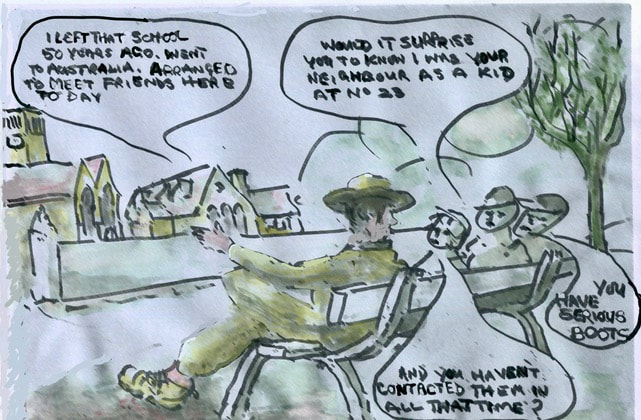

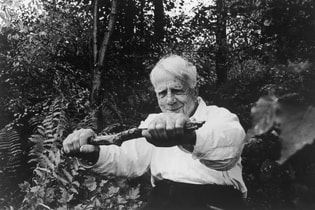

& DISCOVERING THE PLOT'STAYING HOME' The title of this session may sound daunting but we have actually reached a very creative stage of developing the play. We are getting down to finding the plot of each of our four stories. 'Staying Home' 'Leaving Home' 'Displaced' and "Coming Home'. All through the devising process I have tried to accommodate all the ideas and find a pattern, look for ideas that recur, maybe in different ways but essentially have the same theme. For example Evacuees, Refugees, places of refuge, have all come up; as have pilgrimages, journeys, life's paths, the landscape paths of Happy Valley themselves, the purposes of journeys to and from Home, community, sanctuary, safety. Home is our subject, our four stories have themes that reflect Home. Now each of those stories need to be defined and crested as scenes; then we will discover the relationship between those stories to form a concluding scene that ties it all together. The scenes we discover over the coming four fortnightly Wednesdays will be explored on the two intervening Mondays with the improvisation group, and we will report back at the Devising Session. Everyone in the devising group is invited to come and observe the improvisations every second Monday so you can give us your feedback. The improvisers will improvise scenes so that the devises don't have to - but they are, of course, welcome too if they wish. I will start the next devising session talking about possible structures for the whole play, how we might frame and link stories. I will expand on that on Claque's website (click below) After that The first story we will look at is "Staying Home.' The following sessions we will look at two stories each time. NOTES ON DEVISING 28TH APRIL MUSIC & VERSE Becca's, Gilly's and David (our Musical Director's) notes from our Music/Sound Workshop on 28th April. PRESENT; Amy Church, Scott Kingsnorth, Jill Scott, Claire Edwards and Daniel, Paul Fulton, Kate Sargent, Phil Byrne, Sally Sugg, Gilly Blaydon, Mary Jane Stevens, Joe Mendall, Lucy Edkins, Alison Mackenzie, Sonia and Michael Lawrence, Bernie and Julie Madden, David Brett, Jon Oram, Becca Maher. There were problems with zoom so it wasn't possible to go into break out rooms as we had planned. David Jinks wasn't able to join us due to those technical issues. We welcomed Amy who had joined the devising for the first time. She said that at her college she had taken part in a devised piece about homelessness. Song is a good way to tell a story and creating an atmosphere. A song can speak a thousand words. Initially we'll be gathering in the field opposite the church . Not yet decided whether music will be used at that point. What instruments would we like to hear/play? The natural environment such as sticks/rocks/grass make sounds. There will also be other ambient sounds such as dogs barking, people walking/talking. At the large oak tree the four paths diverge: place for poem “The Road Not Taken” Robert Frost. Invisible siren voices luring audience down the different paths. Bells in trees. There’s a branch of the “screaming tree” that swings by itself for a long time – put bells on that. Rocks as instruments. Use the landscape.Daniel: Is a campanologist. Wondered if we could use whatever bells they had in the church. (Later discovered they have one bell.) David has a set of 8 handbells. Bells could be timers to indicate when a group needs to move on. We could add humming to bell ringing. Humming in caves, echoes. Humming might be safer than singing due to covid. Humming is very atmospheric. M.J. Dinner gong, or J. Arthur Rank type gong – can be heard over whole area. She has a djembe ,rain sticks and other percussion instruments and would like to sing too. In Midsummer Night's Dream, Peter Brook used long tubes whirled around the head, like bull roarers. Sally has written a poem about a soldier returning home with combat stress. Sonia has also written two poems on the subject of home which she read to us. Poems condense as do songs. Song "Keep the home fires burning". Home sickness, recognition/tribal music. Small drums to beat a pathway. Military style. Phil can play snare drums. David has drums and other percussion. Involve the Syrian refugees in Tunbridge Wells (T.W Welcomes Refugees). There are Syrian musicians in T.W. They would not need to attend every performance. We could make it clear that singers/musicians would be welcome even if they couldn't attend every performance. We could use a fallen tree as a boat carrying refugees. Alison spoke about a play she saw where the mobile phone was the most important object as the traffickers were going to abandon the migrants at a certain point and they would have to use thir phones to call the coastguard to rescue them. The phone was literally their life line. We could use phones to create sounds. Bath house could have Regency music, or modern songs arranged in Regency style (“Splish Splash”?). Singing in the bath. Voyeurism, audience creeping up to view. Not making any sound can bring tension. Contact singers we know who might be interested. David has mentioned this to a couple of singer contacts who are interested. Paul mentioned a friend who is an opera singer. Familiarity/ recognition is good. But singing songs that are too familiar or obvious might sound a bit too much like busking. Has to be a bit strange and unfamiliar to draw you in. Calling from rock to rock, like a beacon. Street calls. Call and response. We should try one evening with a group, calling across the space to test the acoustics. A performer whispering a poem into your ear.Songs should be simple: chorus, refrain, repetitive. Each story could have a musical theme which is woven into a larger musical piece at the end.Just as the thread of each story is woven into the final story.Involve the Create Choir if possible. Use of phones as backing for songs. wireless speakers which could be used to play music or sound at a distance.Could be used to play birdsong in trees. Amplify the sound of shuffling feet, crunching through leaves and twigs. Or an image first seen as something normal changes to something strange. Image of the Displacement group wearing headphones. Actors listening to headphones , choreographed dance movement to unheard music. Emphasising they are cut off from their environment. Staying home we don't always notice or appreciate where we live. If Happy Valley is the star of the show maybe we shouldn't use too much technology. We want to enhance the features of Happy Valley and use what we find there. All the stories are really about Staying Home. All drama is about this. People don’t take enough notice of their surroundings. MAIN POINTS; 1) We will continue to make Land Art/sculptures throughout the summer.There will be more dates for workshops that will be opened up to a wider audience. 2) Musicians/singers we could involve. David has a friend who is an opera singer and is happy to take part. Maybe contact TW welcomes Refugees regarding Syrian Band. Do we have any friends/contacts who are musicians/singers. Amy, Julie, MJ, Alison, Jill and Bec are happy to sing (but not all happy to sing solo), Jill can play the recorder and Phil drums. 3) Organise music/sound workshops, looking at how sound/music travels in Happy Valley, in caves near rocks etc. 4) Consider songs that relate to the theme of home. 5) Next Devising Workshop Wednesday 12th May 7.30 p.m. Devising Group will be invited fortnightly to join zoom improvisation sessions from Monday 17th May at 7.30 pm. Farewell my dear friend . Peter Terson (Patterson) 'Pete' died in the early hours of April 8th aged 89. He had been living with Parkinson's disease for the last few years, stoic and good natured throughout and supported by his wife Shelia, who has been his rock through their 66 year marriage. Shelia had asked me to write an obituary for their local paper The Ross Gazette in Ross on Wye (See below) but I wanted to add some more reflections on his life and my memories of him. i first met Pete in 1985 at a weekend writers retreat in Monkton Wilde, Dorset that I had set up so I could meet writers and enthuse them about the community play genre. Peter Terson, David Cregan, Nick Darke were among them. I have to confess I was daunted by Pete's energy and frankness, he was a heavy cider drinker at the time and would disappear from the conference with Nick and they would come back somewhat paralytic. As a result I was somewhat nervous and it took five years to invite him to write a play for Bradford on Avon "Under the Fish"and Over The Water (1990) . I then collaborated with him in developing two community operas in Southborough "Have you seen this Girl" (1991) and "Twin Oaks" which were also performed in Lambersart and Lille in France with an Anglo French Cast, directed by Mark Dornford May. I then commissioned him for a second large scale promenade play in 1999, "The Sailors Horse" (Minehead and Watchet). Pete was the most diligent in meeting the community' face to face. These plays can take up to two years to develop. Pete not only made flash visits, the more common approach by busy writers committed to other projects at the same time, he would come and live or holiday in the town with Shelia. As a director I never worked harder having to keep up with Peter. In Minehead he wanted to know about Butlins, both as a holiday maker and behind the scenes, so he insisted I organise a week end stay. We followed the day in the life of a Bluecoat, and the holiday maker, We sang Karaoke, joined a quiz team and played crazy golf with a family, He'd given up drink by then thankfully though we sat in the bars in order to meet the punters and drank juices. Peter watched, listened and most particularly picked up the rhythms, accents, turns-of-phrase of local people. He incorporated these experiences and their personal stories into the play.. The play scripts emerged over the weeks, inspired by events of the previous day or some newly discovered research. Odd scenes would arrive in no particular order. Eventually the full script would arrive in the post. Typed on an old Olivetti typewriter with an old ribbon on various lined, plain yellowing paper or opened envelopes pinned and sellotaped together. There were amicable exchanges of ideas to get to a rehearsal draft, I was to learn that Pete didn't consider a script finished till the show was over. He attended many more rehearsals than any writer and sat on the edge, often with a pile of script papers and listen and watch, seldom interfering. One regular thing he did do ,however ,when a community actor came out with a line in his or her own natural framing, because he or she wasn't yet word perfect, Pete would call out something like "that's not it... "that's not what I wrote" followed by "but. it's better, say it like that." He recognised it sat more comfortably with the actors vernacular, and was therefore more truthful..

`I don't believe in the latter years that Peter Terson got the credit he deserved, Age did not weary him nor did his talent diminish. He was undoubtably one of great playwriting talents of his age. In a self written short biography he wrote that the sixties and seventies were his 'glorious days' a period in which he wrote and had produced somewhere in the region of eighty plays for television, radio and the theatre. He went on to say "but I'm not dead yet and just coming up to my peak `~~(confidence and mad optimism is all to the playwright.) that was Peter Terson to the last, until Parkinson disease robbed him of the capacity to write. Peter Terson's plays are social dramas as relevant today as ever they were. It is beholden on the theatre and those who can to resurrect past plays and produce the more recent ones; we still have a lot to learn from him. He should be as honoured as a dramatist equal to Harold Pinter and Arnold Wesker, especially as he never abandoned his working class roots. OBITUARY |

DIRECTOR'S

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed