|

Jon Oram second left, Keith Johnstone sitting centre, Roddy Maude Roxby seated far right on the Royal Court Stage Theresa Dudeck, writer of 'Keith Johnstone a critical biography' is making a documentary film about Keith Johnstone and organised an on stage interview with the him and some to the original members of Theatre Machine. The Royal Court Theatre was Keith's early theatrical home. He had been appointed Literary Manager of the Court, reading and selecting scripts, when Bill Gaskill invited him to run the writer's workshop 50years ago. The philosophy was not to talk if you could show or do - action over words. So when Edward Bond was struck with the idea that a chair could be a character on stage, the writers had to stand up to demonstrate it. John Arden, David Cregan, Edward Bond, and Ann Jellicoe were among the writer's in the group. It was an extraordinary reunion in the week that Ann died; Keith especially found it a poignant occasion. The writer's group had a huge influence on Ann, the writing of the Knack came directly out of those workshops, and the idea of "don't tell but show" became a big part of her directing as well as writing style. Alongside the writer's group Keith started developing improvisation with actors and formed Theatre Machine. Here they discovered the significance of status to make performance more natural, and many of the games and rules such as "yes..and " are now the fundamental basis of impro. Keith told us " we laughed so much in the writers group I wanted to perform improvisation to audiences to check that it wasn't just us that found it so amusing. The audiences laughed even more, and louder." When Keith left England for Canada in the mid seventies, Theatre Machine continued performing and developing their own style. Roddy Maude Roxby has a big influence on their style, especially with his love of masks. Keith' work and his book Impro has had a dramatic influence worldwide on theatre performance. There was also no improvisation in drama schools then, now its an essential part of the actors training.  Jon Oram and Phelim Mc Dermott Jon Oram and Phelim Mc Dermott In in 1985 when I first took over Colway Theatre from Ann, I ran ten day a course with Keith at Monkton Wilde in Dorset for a select group of twenty actors, directors, writers and drama/theatre teachers. Among the group were Julian Crouch and Phelim McDermott, who were to go on to found Improbable Theatre. Phelim McDermott. Keith introduced 'The Life Game' for the first time on this course. When I ran to Phelim again at this event he told me he "vowed to put on "The Life Game' himself" Twenty years later he made a serious theatre show of it and toured it world wide . Improbable regularly return to it. A collaborator of "Life Game" and Improbable is Lee Simpson who was also at the event. Co-incidently Lee told me he remembers me in Norfolk when I was a drama Advisor and he was still at school. His Drama teacher insisted that we meet me and Lee did an audition for me. Extraordinary he remembered after so many years. I was apparently helpful. Lee Simpson, Jon Oram and Keith Johnstone It was amazing to spend a brief moment with Keith again. I do remember the ten days he taught at Monkton Wilde and how in the evenings he would come back to my house, Rose Cottage, just a short walk away and we'd talk about they day. I learnt more about teaching in those few days than I did in three years of teacher training. We talked about teaching again but mostly about Ann. Keith was genuinely heartbroken, they have been close friends for sixty years, he was unable to attend the funeral because he has a flight back to Canada booked, and he struggles now with walking. As left I told Keith I would be the celebrant at Ann's funeral in a few days and whether he had anything he wanted to say about her. He didn't hesitate - "Yes" he said "Ann always wanted to be truthful, and she always was. Tell them that." I did.

0 Comments

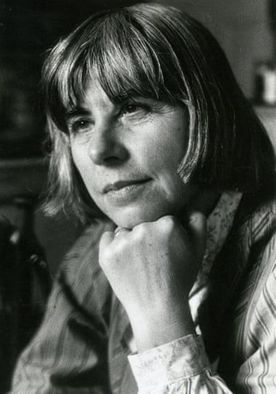

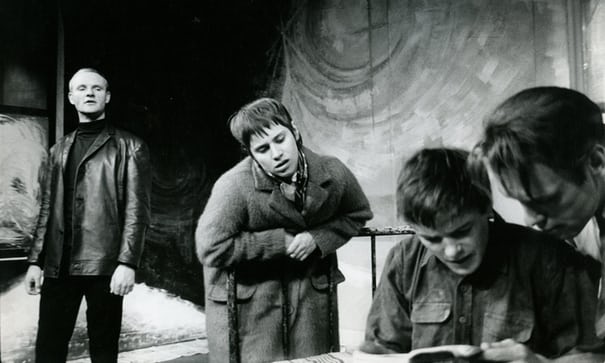

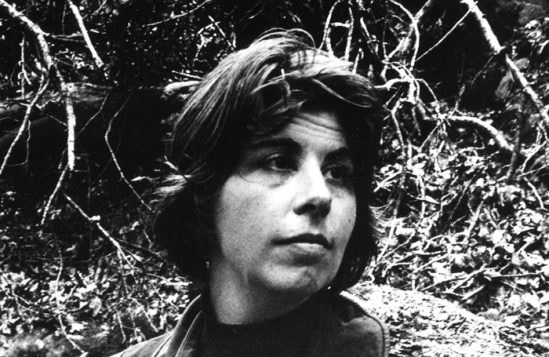

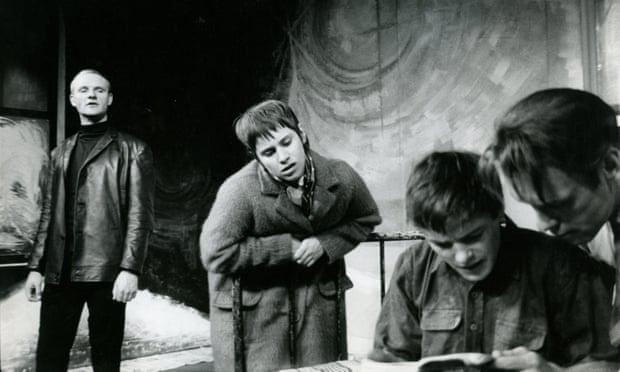

GUARDIAN Ann Jellicoe obituary Michael Coveney and David Edgar Friday 1 September 2017 16.46 BST Last modified on Wednesday 13 September 2017 17.22 BST Playwright and director who scored an international hit with The Knack and pushed the boundaries of community theatre There were two distinct, equally significant, phases to the career of the playwright and director Ann Jellicoe, who has died aged 90. Both were rooted in her dedication to making good theatre of text, and good text of theatre. This led to a slightly conflicted attitude towards her profession that was only fully resolved when she broke clear of the Royal Court – where, in George Devine’s game-changing English Stage Company of the late 1950s, she was a much favoured and respected linchpin, writing two plays that are part of a legendary canon in Sloane Square, The Sport of My Mad Mother (1958) and The Knack (1962). The second of these made an unusual, quirky star of Rita Tushingham on stage and in Richard Lester’s “swinging London” 1965 screen version, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It was only after leaving London for Lyme Regis, Dorset, in 1975 with her husband, the photographer Roger Mayne, and starting what was to become a highly influential career in community theatre that, for the first time, Jellicoe said: “I didn’t feel a divided person.” She wrote a play about the Monmouth rebellion, The Reckoning (1978), for the local comprehensive school, which was staged, with a cast of 80 amateurs and a few professionals, by the University of Exeter, with financial support from local trusts and charities, as well as the local council, which supplied a large banner and plenty of chairs. In 1979 she set up the Colway Theatre Trust to further explore doing plays in the community, producing more than 40 large-scale pieces, including those of major playwrights – David Edgar, Howard Barker, Fay Weldon, Nick Darke – with a south-west of England historical connotation. Subjects included a female brewer’s confrontation with a crusading Dorchester vicar during the cholera epidemic of the 1850s (Edgar’s Entertaining Strangers) and social unrest in the post-Napoleonic industrial slump (Barker’s The Poor Man’s Friend). In 1985 she passed the baton to Jon Oram whose renamed Claque Theatre continues to evolve spectacular “living history” community epics, not only in Devon and Dorset but all over Britain. Rita Tushingham in the Royal Court stage version of The Knack, by Ann Jellicoe, 1962. Photograph: Roger Mayne Archive Jellicoe was born in Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, and grew up there and in Saltburn on the north-east coast, attending Polam Hall school in Darlington and then Queen Margaret’s, Escrick Park, near York, before going to London and the Central School of Speech and Drama as the second world war ended. She was an unhappy child, her father, John Jellicoe, an officer in the armed forces, and mother, Frances (nee Henderson), having separated before she was two. The idea of being an actor was her solace from the age of four. She took dancing lessons and supervised plays and charades throughout her school days. Between 1947 and 1951, after Central, she worked in London and the regions as an actor, stage manager and director. She made a study of the relationship between acting and theatre architecture before founding and directing the Cockpit theatre club to produce experiments on an open, Elizabethan-style stage, the first in London for 400 years. Portrait of Ann Jellicoe by her husband, the photographer Roger Mayne She was invited back to Central in 1953 as a teacher of acting. She stayed for three years while submitting plays, one of them, The Sport of My Mad Mother, to the Observer playwrights’ competition organised by Kenneth Tynan. The play, awarded third prize jointly with NF Simpson’s A Resounding Tinkle, featured a bunch of wild boys given to casual violence, a couple of outsiders and a spiritual leader who gives birth to the creative future. It was, said Tynan, a tour de force that belonged to no known category of theatre, but it was booed off by critics and public alike, and reluctantly withdrawn by Devine after only 14 performances. Devine, who co-directed the play with Jellicoe, recognised in her, said the critic Irving Wardle, a tough professional competence as well as an experimental writing talent. He regarded himself as her “mad uncle” and invited her to join his writers’ group (along with Arnold Wesker, John Arden, Keith Johnstone and Wole Soyinka). She continued writing and also translating, first Ibsen’s Rosmersholm for Devine, starring Peggy Ashcroft and Eric Porter in 1959, and then, in the West End in 1961, Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea, starring Margaret Leighton, Vanessa Redgrave and John Neville. Her 1964 translation (with Ariadne Nicolaeff) of Chekhov’s The Seagull for the English Shakespeare Company at the Queen’s was an unforgettable occasion, starring Devine as Dorn, Ashcroft as Arkadina, Peter Finch as Trigorin, Redgrave as Nina, and Peter McEnery as Konstantin. By then, she had scored a bull’s-eye with The Knack, which she co-directed with Keith Johnstone; James Bolam, Julian Glover and Philip Locke were the three men circling Tushingham as the girl who comes to the house they share. The play was an international hit and was directed in New York by Mike Nichols. When William Gaskill took over as the Court’s artistic director in 1965, following Devine’s death, he opened with Jellicoe’s production of her own Shelley, a documentary-style biography of the poet wrestling with notions of goodness, the rejection of creative artists and the place of women – Shelley was portrayed as a misogynist. Described by one critic as “a strange, almost wilfully unappealing play”, it was followed by Simpson’s The Cresta Run and two other equally snubbed but embryonic classics – Edward Bond’s Saved and John Arden’s Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance. After her first play bombed, Jellicoe had nonetheless been approached by the Girl Guides Association to write a spectacle for a cast of hundreds. In The Rising Generation, girls were urged to reject men and claim Shakespeare, Milton and Isaac Newton as female. Unsurprisingly, the Girl Guides rejected the play, but it surfaced briefly as a Sunday night show “without decor” at the Court in 1967 – with three actors and a mere 200 children – in what Jellicoe described as “the most successful first night I ever had”, thus leading her to think more along the lines of plays in the community. The Reckoning, Ann Jellicoe’s first community play, in Lyme Regis, Dorset, 1978. Photograph: Roger Mayne Archive She briefly took a more commercial tack in a West End comedy, The Giveaway (1968) at the Garrick, in which another plot of sexual siege-laying was wrapped in an absurdist scenario of a family who had won a 10-year supply of breakfast cereal contained in eight huge on-stage crates. After a break to have two children, she was invited back to the Court as literary manager, and directed there Paul Bailey’s A Worthy Guest (1974) as well as a series of children’s plays (“Jelliplays”), before decamping for good to Dorset with her family. She wrote several community plays for her new company and a fine practical handbook, Community Plays: How to Put Them On (1987). Her productions always had a core of professionals – usually the writer, director, composer and designer – but everything else was done by and with the community.

After stepping down from running the Colway Theatre Trust, she still wrote for the organisation as it widened its geographical net beyond the south-west: Changing Places (1992) was a play about suffrage in Woking, Surrey, and its local heroine, the composer Dame Ethel Smyth. Her first marriage ended in divorce. Mayne, whom she married in 1962, died in 2014. She is survived by their daughter, Katkin, and son, Tom. Michael Coveney David Edgar writes: In 1984, I was invited to Lyme Regis, Dorset, to see Ann Jellicoe’s fourth community play, The Western Women. I’d known of this work but was unprepared for its overwhelming impact in practice. I was asked to be the writer on the next-but-one play, and accepted immediately. Ann was aware of the sensitivities of the communities she worked with, but also of the likely politics of the playwrights she would attract. She told me that, if I had to make the play about wicked capitalists, it would be best if they came from out of town. In fact, we came up with a story of a titanic struggle between a pioneering woman brewer and a fundamentalist parson. Entertaining Strangers: A Play for Dorchester was performed in St Mary’s, the church the vicar founded, with more than 100 community actors. The play was remounted at the National Theatre in 1987, with Judi Dench and Tim Pigott-Smith in the leads. The revival fed a myth that Ann’s method was essentially colonial, airlifting in her fancy theatrical friends to impose their vision on the community and move on. In fact, Dorchester is the best possible example of the long-term impact of the form: my play has been followed by six more, with a seventh (by Stephanie Dale) coming up. The Ansell family – three generations, participating in every Dorchester play so far – is a prime example of how Ann’s community plays changed lives. • Patricia Ann Jellicoe, playwright and director, born 15 July 1927; died 31 August 2017 Michael Coveney and David Edgar The Guardian 1st September 2017 Playwright and director who scored an international hit with The Knack and pushed the boundaries of community theatre. There were two distinct, equally significant, phases to the career of the playwright and director Ann Jellicoe, who has died aged 90. Both were rooted in her dedication to making good theatre of text, and good text of theatre. This led to a slightly conflicted attitude towards her profession that was only fully resolved when she broke clear of the Royal Court – where, in George Devine’s game-changing English Stage Company of the late 1950s, she was a much favoured and respected linchpin, writing two plays that are part of a legendary canon in Sloane Square, The Sport of My Mad Mother (1958) and The Knack (1962). The second of these made an unusual, quirky star of Rita Tushingham on stage and in Richard Lester’s “swinging London” 1965 screen version, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It was only after leaving London for Lyme Regis, Dorset, in 1975 with her husband, the photographer Roger Mayne, and starting what was to become a highly influential career in community theatre that, for the first time, Jellicoe said: “I didn’t feel a divided person.” She wrote a play about the Monmouth rebellion, The Reckoning (1978), for the local comprehensive school, which was staged, with a cast of 80 amateurs and a few professionals, by the University of Exeter, with financial support from local trusts and charities, as well as the local council, which supplied a large banner and plenty of chairs. In 1979 she set up the Colway Theatre Trust to further explore doing plays in the community, producing more than 40 large-scale pieces, including those of major playwrights – David Edgar, Howard Barker, Fay Weldon, Nick Darke – with a south-west of England historical connotation. Subjects included a female brewer’s confrontation with a crusading Dorchester vicar during the cholera epidemic of the 1850s (Edgar’s Entertaining Strangers) and social unrest in the post-Napoleonic industrial slump (Barker’s The Poor Man’s Friend). In 1985 she passed the baton to Jon Oram whose renamed Claque Theatre continues to evolve spectacular “living history” community epics, not only in Devon and Dorset but all over Britain Rita Tushingham in the Royal Court stage version of The Knack, by Ann Jellicoe, 1962. Photograph: Roger Mayne Archive  Jellicoe was born in Middlesbrough, North Yorkshire, and grew up there and in Saltburn on the north-east coast, attending Polam Hall school in Darlington and then Queen Margaret’s, Escrick Park, near York, before going to London and the Central School of Speech and Drama as the second world war ended. She was an unhappy child, her father, John Jellicoe, an officer in the armed forces, and mother, Frances (nee Henderson), having separated before she was two. The idea of being an actor was her solace from the age of four. She took dancing lessons and supervised plays and charades throughout her school days. Between 1947 and 1951, after Central, she worked in London and the regions as an actor, stage manager and director. She made a study of the relationship between acting and theatre architecture before founding and directing the Cockpit theatre club to produce experiments on an open, Elizabethan-style stage, the first in London for 400 years She was invited back to Central in 1953 as a teacher of acting. She stayed for three years while submitting plays, one of them, The Sport of My Mad Mother, to the Observer playwrights’ competition organised by Kenneth Tynan. The play, awarded third prize jointly with NF Simpson’s A Resounding Tinkle, featured a bunch of wild boys given to casual violence, a couple of outsiders and a spiritual leader who gives birth to the creative future. It was, said Tynan, a tour de force that belonged to no known category of theatre, but it was booed off by critics and public alike, and reluctantly withdrawn by Devine after only 14 performances. Devine, who co-directed the play with Jellicoe, recognised in her, said the critic Irving Wardle, a tough professional competence as well as an experimental writing talent. He regarded himself as her “mad uncle” and invited her to join his writers’ group (along with Arnold Wesker, John Arden, Keith Johnstone and Wole Soyinka). She continued writing and also translating, first Ibsen’s Rosmersholm for Devine, starring Peggy Ashcroft and Eric Porter in 1959, and then, in the West End in 1961, Ibsen’s The Lady from the Sea, starring Margaret Leighton, Vanessa Redgrave and John Neville. Her 1964 translation (with Ariadne Nicolaeff) of Chekhov’s The Seagull for the English Shakespeare Company at the Queen’s was an unforgettable occasion, starring Devine as Dorn, Ashcroft as Arkadina, Peter Finch as Trigorin, Redgrave as Nina, and Peter McEnery as Konstantin. By then, she had scored a bull’s-eye with The Knack, which she co-directed with Keith Johnstone; James Bolam, Julian Glover and Philip Locke were the three men circling Tushingham as the girl who comes to the house they share. The play was an international hit and was directed in New York by Mike Nichols. When William Gaskill took over as the Court’s artistic director in 1965, following Devine’s death, he opened with Jellicoe’s production of her own Shelley, a documentary-style biography of the poet wrestling with notions of goodness, the rejection of creative artists and the place of women – Shelley was portrayed as a misogynist. Described by one critic as “a strange, almost wilfully unappealing play”, it was followed by Simpson’s The Cresta Run and two other equally snubbed but embryonic classics – Edward Bond’s Saved and John Arden’s Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance. After her first play bombed, Jellicoe had nonetheless been approached by the Girl Guides Association to write a spectacle for a cast of hundreds. In The Rising Generation, girls were urged to reject men and claim Shakespeare, Milton and Isaac Newton as female. Unsurprisingly, the Girl Guides rejected the play, but it surfaced briefly as a Sunday night show “without decor” at the Court in 1967 – with three actors and a mere 200 children – in what Jellicoe described as “the most successful first night I ever had”, thus leading her to think more along the lines of plays in the community. She briefly took a more commercial tack in a West End comedy, The Giveaway (1968) at the Garrick, in which another plot of sexual siege-laying was wrapped in an absurdist scenario of a family who had won a 10-year supply of breakfast cereal contained in eight huge on-stage crates. After a break to have two children, she was invited back to the Court as literary manager, and directed there Paul Bailey’s A Worthy Guest (1974) as well as a series of children’s plays (“Jelliplays”), before decamping for good to Dorset with her family. She wrote several community plays for her new company and a fine practical handbook, Community Plays: How to Put Them On (1987). Her productions always had a core of professionals – usually the writer, director, composer and designer – but everything else was done by and with the community. After stepping down from running the Colway Theatre Trust, she still wrote for the organisation as it widened its geographical net beyond the south-west: Changing Places (1992) was a play about suffrage in Woking, Surrey, and its local heroine, the composer Dame Ethel Smyth. Her first marriage ended in divorce. Mayne, whom she married in 1962, died in 2014. She is survived by their daughter, Katkin, and son, Tom. Michael Coveney David Edgar writes: In 1984, I was invited to Lyme Regis, Dorset, to see Ann Jellicoe’s fourth community play, The Western Women. I’d known of this work but was unprepared for its overwhelming impact in practice. I was asked to be the writer on the next-but-one play, and accepted immediately. Ann was aware of the sensitivities of the communities she worked with, but also of the likely politics of the playwrights she would attract. She told me that, if I had to make the play about wicked capitalists, it would be best if they came from out of town. In fact, we came up with a story of a titanic struggle between a pioneering woman brewer and a fundamentalist parson. Entertaining Strangers: A Play for Dorchester was performed in St Mary’s, the church the vicar founded, with more than 100 community actors. The play was remounted at the National Theatre in 1987, with Judi Dench and Tim Pigott-Smith in the leads. The revival fed a myth that Ann’s method was essentially colonial, airlifting in her fancy theatrical friends to impose their vision on the community and move on. In fact, Dorchester is the best possible example of the long-term impact of the form: my play has been followed by six more, with a seventh (by Stephanie Dale) coming up. The Ansell family – three generations, participating in every Dorchester play so far – is a prime example of how Ann’s community plays changed lives. • Patricia Ann Jellicoe, playwright and director, born 15 July 1927; died 31 August 2017 |

DIRECTOR'S

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed