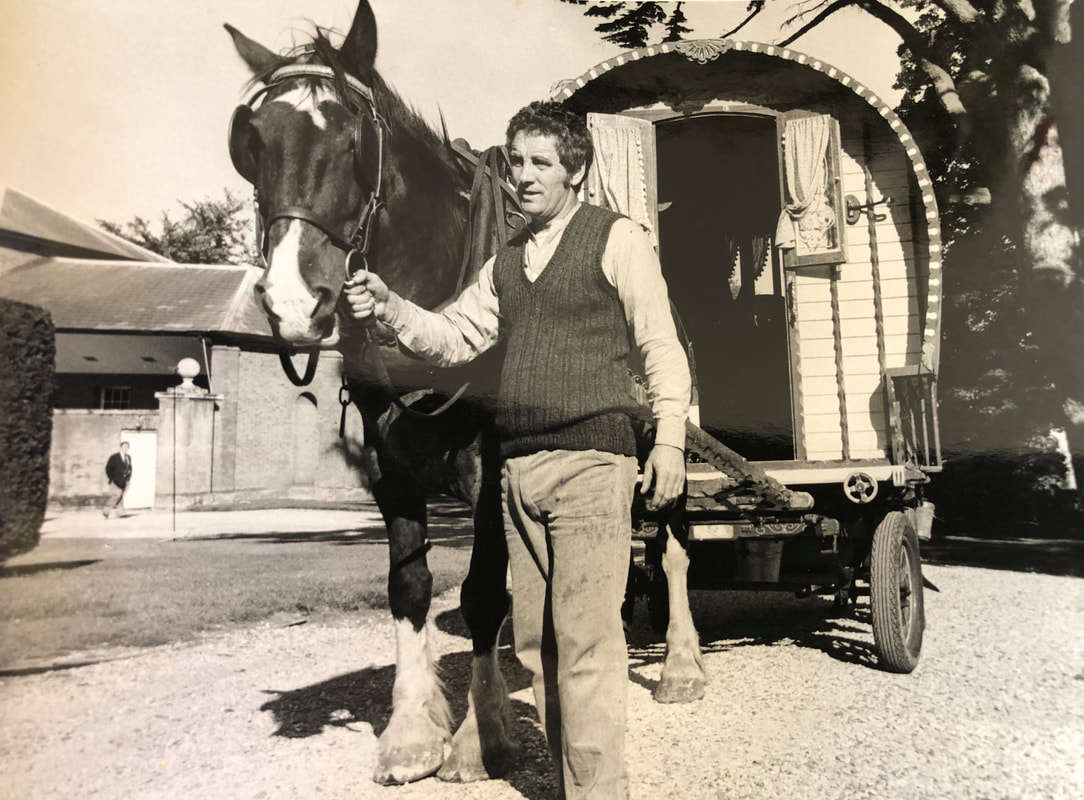

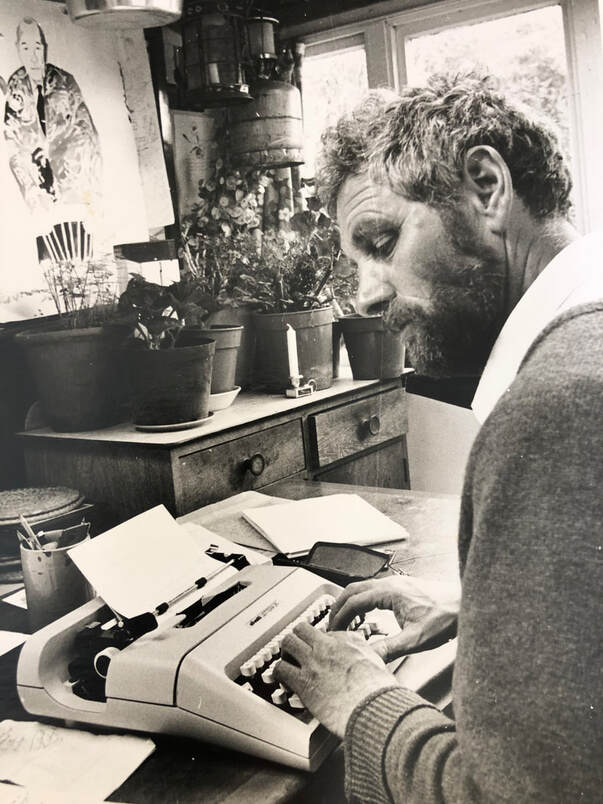

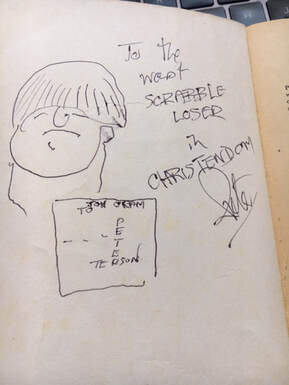

Farewell my dear friend . Peter Terson (Patterson) 'Pete' died in the early hours of April 8th aged 89. He had been living with Parkinson's disease for the last few years, stoic and good natured throughout and supported by his wife Shelia, who has been his rock through their 66 year marriage. Shelia had asked me to write an obituary for their local paper The Ross Gazette in Ross on Wye (See below) but I wanted to add some more reflections on his life and my memories of him. i first met Pete in 1985 at a weekend writers retreat in Monkton Wilde, Dorset that I had set up so I could meet writers and enthuse them about the community play genre. Peter Terson, David Cregan, Nick Darke were among them. I have to confess I was daunted by Pete's energy and frankness, he was a heavy cider drinker at the time and would disappear from the conference with Nick and they would come back somewhat paralytic. As a result I was somewhat nervous and it took five years to invite him to write a play for Bradford on Avon "Under the Fish"and Over The Water (1990) . I then collaborated with him in developing two community operas in Southborough "Have you seen this Girl" (1991) and "Twin Oaks" which were also performed in Lambersart and Lille in France with an Anglo French Cast, directed by Mark Dornford May. I then commissioned him for a second large scale promenade play in 1999, "The Sailors Horse" (Minehead and Watchet). Pete was the most diligent in meeting the community' face to face. These plays can take up to two years to develop. Pete not only made flash visits, the more common approach by busy writers committed to other projects at the same time, he would come and live or holiday in the town with Shelia. As a director I never worked harder having to keep up with Peter. In Minehead he wanted to know about Butlins, both as a holiday maker and behind the scenes, so he insisted I organise a week end stay. We followed the day in the life of a Bluecoat, and the holiday maker, We sang Karaoke, joined a quiz team and played crazy golf with a family, He'd given up drink by then thankfully though we sat in the bars in order to meet the punters and drank juices. Peter watched, listened and most particularly picked up the rhythms, accents, turns-of-phrase of local people. He incorporated these experiences and their personal stories into the play.. The play scripts emerged over the weeks, inspired by events of the previous day or some newly discovered research. Odd scenes would arrive in no particular order. Eventually the full script would arrive in the post. Typed on an old Olivetti typewriter with an old ribbon on various lined, plain yellowing paper or opened envelopes pinned and sellotaped together. There were amicable exchanges of ideas to get to a rehearsal draft, I was to learn that Pete didn't consider a script finished till the show was over. He attended many more rehearsals than any writer and sat on the edge, often with a pile of script papers and listen and watch, seldom interfering. One regular thing he did do ,however ,when a community actor came out with a line in his or her own natural framing, because he or she wasn't yet word perfect, Pete would call out something like "that's not it... "that's not what I wrote" followed by "but. it's better, say it like that." He recognised it sat more comfortably with the actors vernacular, and was therefore more truthful..

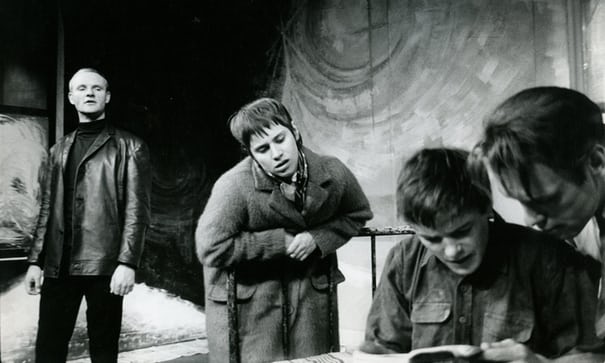

`I don't believe in the latter years that Peter Terson got the credit he deserved, Age did not weary him nor did his talent diminish. He was undoubtably one of great playwriting talents of his age. In a self written short biography he wrote that the sixties and seventies were his 'glorious days' a period in which he wrote and had produced somewhere in the region of eighty plays for television, radio and the theatre. He went on to say "but I'm not dead yet and just coming up to my peak `~~(confidence and mad optimism is all to the playwright.) that was Peter Terson to the last, until Parkinson disease robbed him of the capacity to write. Peter Terson's plays are social dramas as relevant today as ever they were. It is beholden on the theatre and those who can to resurrect past plays and produce the more recent ones; we still have a lot to learn from him. He should be as honoured as a dramatist equal to Harold Pinter and Arnold Wesker, especially as he never abandoned his working class roots. OBITUARY |

DIRECTOR'S

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed